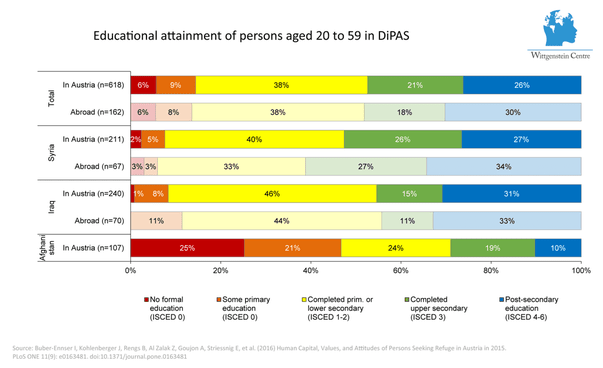

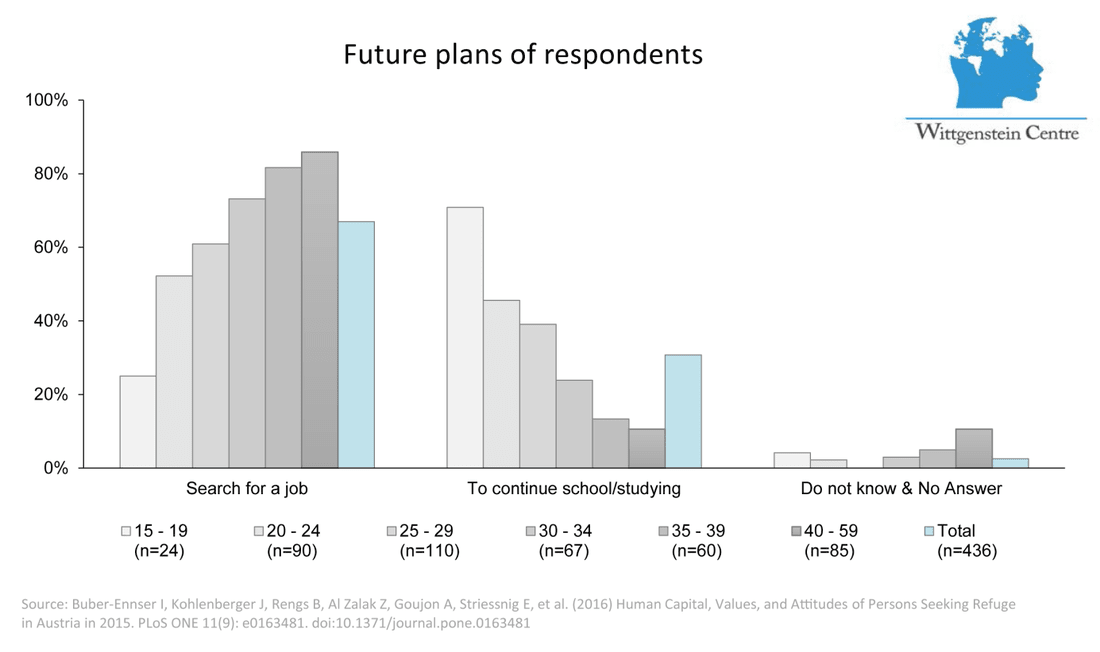

Judith Kohlenberger & Isabella Buber-Ennser Across Europe, the time between late summer and fall 2015 became rapidly known as the so-called ‘refugee crisis’, exposing us to daily pictures of large numbers of forced migrants crossing the borders to the EU on foot or by train. Between July and December, roughly 60,000 asylum applications were filed in Austria, amountingaltogether to 88,098 applications by the end of the year.[i] Most of these asylum seekers fled from persecution, war and torture in their home countries Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, which account for 71% of all asylum applications in 2015.[ii] Contrary to popular discourse and tabloid media reports, however, the forced migrants who arrived in Austria in fall 2015 were far from a homogenous group, nor were they a random sample: Research has impressively shown that the Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans who sought refuge in Austria display very specific socio-demographic characteristics, from educational levels and professional qualifications to attitudes and values. To tailor civil society efforts, NGOs’ relief services and national integration policies to the specific aims and needs of forced migrants, the question should thus not only be How many are coming?, but more significantly: Who is coming? Moving beyond counting heads to studying what’s in these heads in terms of knowledge, training and skills is exactly what a recent quantitative study at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, WU) tried to achieve. DiPAS (Displaced Persons in Austria Survey) was launched in October 2015 under the supervision of Wittgenstein Prize laureate Wolfgang Lutz, with the aim of uncovering the socio-demographic characteristics of asylum seekers in Austria. The survey, the first of its kind in Austria, was carried out among displaced adults, mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, who had recently arrived in Austria. Face‐to‐face interviews were conducted in seven NGO-run refugee shelters in and around Vienna to question respondents about their origins, education attainment and professional experience, marital status, attitudes and values as well as their future plans. The survey yielded 514 completed interviews and also gathered information on respondents’ spouses and children, which allowed for the analysis of 1,391 persons altogether. This analysis showed that asylum seekers who entered Austria in summer and fall 2015 are well-educated, hold less traditional values than their compatriots and have a predominantly middle-class background, when compared with respective data from the countries of origin. About a quarter of respondents from Syria and Iraq had obtained a post-secondary degree. This corresponds to the percentage of people with a specialized high‐school diploma (“Fachmatura”) or a higher education degree in Austria. Nearly half of the forced migrants in the sample completed an upper secondary education. This percentage is considerably higher than among the general population in their respective home countries, where the figures are closer to 10% (Afghanistan) and 20% (Syria), respectively.[iii] Socioeconomic factors furthermore indicate that a large share of respondents came from middle-class backgrounds before the humanitarian crisis forced them to flee their countries. Home ownership was very common: Four-fifths of respondents lived in their own or their family’s house before they had to flee. The majority of respondents indicated that they had to pay between US$ 2,000 and 3,000 for their journey, which roughly corresponds to the average annual income in Syria and Iraq before the crisis propelled heavy inflation and falling exchange rates. Results further show that the surveyed population comprised mainly young families with children, particularly among Syrians and Iraqis. When extrapolating the number of children or partners still in their home country, the potential for family reunifications can be estimated, ranging at 38 (nuclear) family members per 100 refugees. Sensible international policy measures for safe and quick family reunification are pertinent, not least because, for the majority of forced migrants, their resettlement may very well be a permanent one: Two-thirds of respondents do not intend to return to their home countries, mostly because of the perception of permanent threat. The intention to return is highest among Syrian respondents, which may indicate particularly strong ties with and a high emotional attachment to the home country.  Concerning plans for their future in Austria, most respondents intend to search for a job, which correlates with high levels of previous employment experience, especially among male asylum seekers. Quite consistently, this result is age-specific: In the relevant age groups of 15–19 years and 20–24 years, the majority of respondents wish to complete their education before entering the Austrian labor market. This may suggest an appreciation for the value of (higher) education for one’s personal and professional future, an interpretation supported by the overall high levels of education among older respondents. The data collected for DiPAS allow for many more insights on who the forced migrants from fall 2015 are, ranging from respondents’ religion, their levels of religiosity and self-assessed health to attitudes and values on issues of gender equity and household task sharing. The more we learn about the demographics of recent refugee arrivals to Austria, the better, faster and more efficiently resources can be directed to those in need. While DiPAS is only a small, yet significant piece of a bigger puzzle, we hope that further country-specific, as well as international, comparative studies will soon all contribute to establishing a more differentiated, individualized picture of refugees in Europe. Only such a nuanced picture can do justice to the complexity of forced migrant experiences, their hopes and needs. Notes: [i] BMI. Asylstatistik 2015 [Asylum statistics 2015]. Vienna: Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior; 2016. Available at <http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/bmi_service/>. (accessed 13 Dec. 2016). [ii] Ibid. [iii] Data provided by the Central Bureau of Statistics (2004) for Syria and the Central Statistics Organization for Afghanistan. No recent representative survey is available for the Iraqi population.

2 Comments

|

Archives

June 2022

|

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder, except for the inclusion of quotations properly cited.

Published in Vienna, Austria by ROR-n.