|

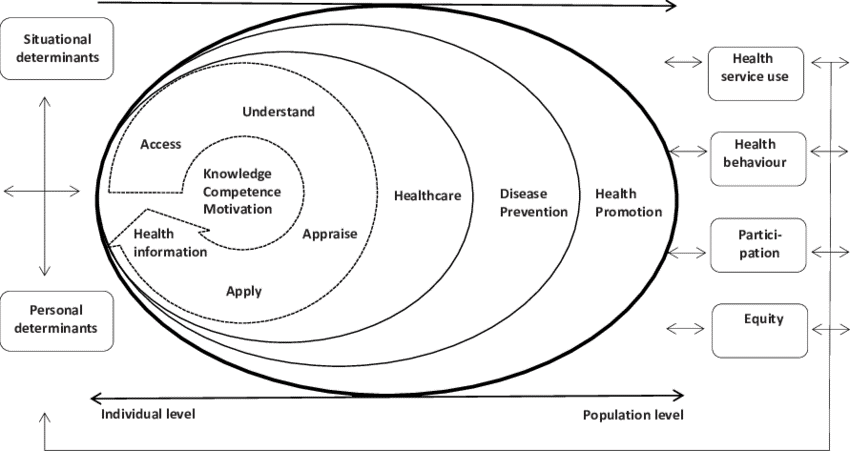

By Julia Volk Health literacy – competences that enable access, evaluation and application of knowledge about health - is gaining importance in public health as well as in politics. Although being a refugee means a higher risk in having bad health literacy, there is little data on refugees who live in Austria. The following is a synopsis of my master thesis (Volk 2017), which aims at gaining knowledge of health literacy of refugees and defining fields of action for occupational therapists to promote the health literacy of this “target group”. To this end, I have interviewed two refugees (a Syrian couple), two occupational therapists (working in this field) and two so-called “experts” (researchers from "Gesundheit Österreich GmbH" and "Salus Gesundheitslotsinnen"). The term health literacy, as used in this work, refers to the model developed by Sorensen et al. in 2012 through a systematic literature review. As shown in the image below, health literacy consists of internal motivation, competences and knowledge that allow a person to access, understand, appraise and apply health-related information within external determinants of the health system. Health literacy is an unequally distributed but influenceable social determinant that follows a social gradient and causes – among many other things – health inequity. In the light of its relational conception, there are two levels that influence health literacy: an individual level – with personal and individual skills and competences – and a systematic level – with the demands and the complexity of the system a person is living in. Being a refugee carries a higher risk in having bad health literacy, which can be attributed to a lack of proficiency in the language of the host country, to a lack of cultural/systematic knowledge and to socio-economic factors. Such refugee-specific aspects as sense of home or residence permit status play a comparatively small role. The interviewed couple who fled from Syria to Austria has limited health literacy according to every of Sorensen’s defined variables – access, understanding, appraisal and application of health-related information. Reasons for that are the complexity of medical language, stigmatization during medical treatment, financial disadvantages and obstructive frame conditions. Moreover, the interviewed refugees themselves name occupational deprivation and unemployment as their personal reasons for their poor health literacy.

This indicates that occupational therapy can promote the health literacy of refugees. In my work, I have identified the following fields of action for occupational therapists in promoting the health literacy of refugees:

The latter assists group dynamic processes that allow people to build social networks. Moreover, activities in groups serve as a medium for communication and facilitate interaction automatically through the activity, which is of additional value. Occupational therapy promotes three sets of meaningful benefits in the work with refugees. First, there is the client-centered approach. Unlike the impression created by the media, the “group of refugees” is very heterogeneous in itself. Working with refugees, therefore, means taking a sophisticated and client-centered perspective to develop individual purposeful solutions. Second, there is the holistic and bio-psycho-social mind-set and the competence to consider and treat both physical and mental illnesses, while taking into account the social, cultural and physical environment. This aspect is especially important in the work with people who were forced to flee and suffer from traumas. Finally, the absolute USP (unique selling proposition) is that of connecting health and occupation, and promoting health and quality of life through meaningful activities. The refugees themselves named lack of meaningful activities as one of two causes for their limited health literacy. Considering these factors, it is incomprehensible why occupational therapists are not part of the work with refugees in the Austrian health system. One of the interviewed occupational therapists mentioned the following obstacles this professional group faces in the attempt to gain a foothold in the work with refugees: language, financing and biases inherent in the system. One such bias is that while psychotherapists and social workers are recognized as an “authorized” professional group in the work with refugees and are recompensed for their expertise, this is not the case for occupational therapists. These challenges absolutely need to be overcome. A few occupational therapists work – mainly as volunteers – in this field. The following may serve as a rare best-practice example of occupational therapeutic work with refugees in Austria: Bike2gether was a bicycle-repair-shop initiated in an emergency accommodation for refugees in Vienna in the summer of 2016 with the aim to promote meaningful activities for the inhabitants and to broaden their scope of action. This project addressed four important factors: doing (activities), being (getting a new and meaningful role in life), becoming (activities gain meaning through becoming) and belonging (gaining new social contacts, becoming part of a community and discovering new fields of action). This intervention by occupational therapists aimed at promoting occupational balance and occupational justice. And, therefore, it promoted health literacy as well. Finally, I would like to mention a study by an occupational therapist, who has investigated occupational deprivation of unattended underage refugees in Tyrol in 2015. She found out that lack of financial resources and being forced “to do nothing”, a state called “occupational deprivation” in the terminology of occupational therapists, diminishes health and quality of life. A daily life that is determined by dependence, loss of control and isolation causes a loss of motivation, well-being and the expectation of self-efficacy, which in turn lead to the feeling of being ill. Besides that, such environmental factors as bad living conditions, missing education and social networks have a negative impact on the health of refugees. These findings again illustrate the interaction of internal and external factors and their influence on health. They also emphasize that meaningfulness is essential for health and quality of life. Generated by individual meaningful activities, manageability and comprehensibility, it may be enhanced or restrained by the system. That is why – in addition to the necessary stress on systematic conditions – the focus on the promotion of meaningful activities of refugees through occupational therapeutic work is so important for the promotion of health and health literacy. These meaningful activities play an important role for everybody's health but are often forgotten, especially when it comes to refugees. Occupational justice must be seen as a dimension of health equity that includes the right of performing meaningful activities! Bibliography Außermaier H. (2016). Bedeutungsvolle Betätigung als Schlüssel zur ergotherapeutischen Gesundheitsvorsorge und Prävention bei Geflüchteten. ergotherapie. Fachzeitschrift von Ergotherapie Austria – Berufsverband der Ergotherapeutinnen und Ergotherapeuten Österreichs. S. 22-27. Costa, U., Pasqualoni, P. P., Wetzelsberger, B. (2016). Betätigungsgerechtigkeit als Dimension gesundheitlicher Chancengerechtigkeit: Handlungswissenschaftliche Zugänge. Forschungsforum der österreichischen Fachhochschulen. Verfügbar unter: http://ffhoarep.fhooe.at/handle/123456789/691. Fritz, J., Tomaschek, N. (2016). Gesellschaft im Wandel: Gesellschaftliche, wirtschaftliche und ökologische Perspektiven. Waxmann Verlag. S. 127. Ganahl, K., Dahlvik, J., Räthlin, F.; Alpagu, F.; Sikic-Fleischhacker, A.; Peer, S, Pelikan, J.M. (2016): Gesundheitskompetenz bei Personen mit Migrationshintergrund aus der Türkei und Ex-Jugoslawien in Österreich. Ergebnisse einer quantitativen und qualitativen Studie. LBIHPR Forschungsbericht. Kickbusch, I., Pelikan, J., Haslbeck, J., Apfel, F., Tsouros, A.D. (2013): Gesundheitskompetenz. Die Fakten. Careum Stiftung Schweiz. S. 10-90f. Parker, R., Ratzan, S. C. (2010). Health literacy: A second decade of distinction for Americans. Journal of Health Communication; 15(Suppl. 2): 20-33. Sorensen, K., Van de Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., Brand, H.(2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. Verfügbar unter: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/80. Steiner, M., Weitzhofer, E. (2014). Sinnvolle Betätigungsmöglichkeiten für AsylwerberInnen schaffen. Verfügbar unter: http://betaetigung.weebly.com/ergotherapie-austria.html. Volk, J. (2017). Gesundheitskompetenz von Flüchtlingen. Eine qualitative Analyse der Gesundheitskompetenz von syrischen Flüchtlingen in Österreich.

2 Comments

|

Archives

June 2022

|

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder, except for the inclusion of quotations properly cited.

Published in Vienna, Austria by ROR-n.