|

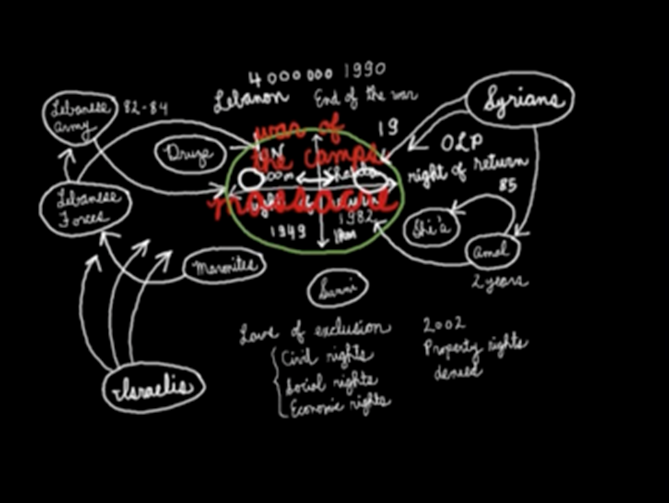

By Gustavo Barbosa *This essay presents one of the arguments developed by the author in his book The Best of Hard Times: Palestinian Refugee Masculinities in Lebanon (Barbosa, 2022). In this short essay, I argue for the full historicity and pliability of masculinity, which changes from place to place and time to time. Based on fieldwork conducted in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in the southern outskirts of Beirut, where I lived for one year and conducted research for two, I demonstrate that the shabāb, the lads from the camp, faced with unemployment and the de-mobilization of the Palestinian Resistance movement, in its military form, cannot replicate the heroic persona of their forebears, the fidāʾiyyīn, who exude virility when narrating their deeds. As may be implied from this already, based on shabāb’s biographies, I problematize what Marcia Inhorn (2012) has ironically labelled “hegemonic masculinity, Middle Eastern style.” I develop my argument in three moves. First, I provide the reader with historic scaffolding, so that s/he can understand not only why masculinity has changed from one generation to the next, but also why gender, as a concept imbued with notions of power, works well to describe the fidāʾiyyīn’s lives, but not the shabāb’s. Second, I provide some ethnographic evidence to this argument. I finish by addressing some of the theoretical implications of my reasoning. For the historic scaffolding, I quote from what I consider as the best documentary about Shatila, the movie Roundabout Shatila (2005), by Maher Abi Samra. Even though a bit dated, the quote, illustrated by the film frame below, shows how Shatila is placed at the centre of various circles of causation, all highly complex. That means, in practice, that Shatilans today, including the shabāb, have very little control of what at the end comes to determine their lives. Figure 1 – Frame from the movie Roundabout Shatila, by Maher Abi Samra “Shatila Camp, one kilometer long and 600 meters large, is located in the outskirts of the southern suburb of Beirut. In 1949, the UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Middle East) leased the camp in order to house the Palestinian refugees waiting for their right of return. Lebanon is a sectarian society of approximately four million people and 19 religious communities. The principal ones are the Shiites, the Maronites, the Sunnites and the Druze. These communities have always relied on alliances with powerful foreign countries to protect their own interests. Consequently, the Israelis and the Syrians continue to play a leading role in Lebanon. In 1982, the Israeli Army invades Lebanon. The PLO (the Palestinian Liberation Organization) is forced to leave Lebanon. Maronite militias, known as the Lebanese Forces, backed by the Israelis, commit the Sabra and Shatila massacres. It is the end of one period and the beginning of another. The official Lebanese Army, backed by the Lebanese Forces, surround the camp of Shatila between 1982 and 1984. During this period, the Army conducts forcible house searches and massive arrests. In 1985, Amal, the Shiite militia, backed by the Syrian regime, start the War of the Camps and surround the camp for two years. Two years later, Amal can still not retain Shatila. Palestinian organizations, backed by the Syrians, start an internal conflict between Palestinians, which ends with total Syrian regime control of the camp that continues to this day. 1990 marks an end to the Lebanese Civil War. Shatila is still under Syrian control. The laws which deprive Palestinians of their civil rights, social rights, and economic rights are enforced again. Though deeply divided on other issues, Lebanese society holds the Palestinians solely responsible for the Civil War. In 2002, the majority of the Lebanese Parliament votes to deny the right of property to Palestinians. The pretext invoked is to protect the Lebanese identity and the stability of the sectarian system, but the underlying reason is to retain the Palestinians’ right of return. Shatila and other refugee camps in Lebanon have become the scapegoat of Lebanese society.” Two different iconic figures are associated with each of these historic periods. As shown in the quote from Abi Samra’s movie, the important year to remember here is 1982, the definitive turning point in this saga. Before that year was the period that Palestinians refer to as the golden days of the revolution, the ayyām al-thawra, their moment of strength in Lebanon. The iconic figure associated with this period is the resistance fighter, the fidāʾī. The very word means the man who is willing to sacrifice himself, in the fight to reconquer the motherland. Posters from this period often celebrated this figure, portraying him in all his courage and pride walking on the crest of hills, a kuffiyya, the Arab strap around his shoulders, and a bunduqiyya, the Kalashinikov machine-gun in his hand, proceeding to military incursions deep into Palestine. With the end in 1982 of the days of the revolution, the iconic figure became the camp shāb, the lad from Shatila, who cannot act as a fighter, because the Palestinian Resistance Movement was de-mobilized, and who cannot find a job either and, as a result, needs to postpone marriage plans. The changes in the iconic figures of these two periods – the brave fidāʾī and the shāb with very limited access to power – speaks to the full historicity and pliability of masculinity. In Palestine, before 1948, a man would come of age and display his gender belonging by marrying, starting an independent household and bearing a son. For the Palestinian diaspora in Lebanon, prior to 1982, acting as a fidāʾī provided an alternative mechanism for men to come of age and display gender belonging. But, then, what happens to today’s shabāb, who cannot act as male providers for the families they wish to start or act as fighters? Based on the specialized literature, the traditional answer to this question is that the shabāb are emasculated, that their masculinity is in crisis because they cannot live up to the requirements of an ideal-typical hegemonic masculinity. But, by living with them in Shatila, I did not get the feeling that they thought that their masculinity was menaced. So, rather than freezing ideals of masculinity and creating crisis by heuristic fiat, I decided, following Inhorn’s advice, to nuance the discussion of the masculine ideal, opening it up to the findings of my ethnography. At the end, these findings prompted me to provoke another crisis, of an epistemological nature: the crisis of gender as a concept. The time has come to populate this history and this discussion with ethnography and real life. A fidāʾī’s and a shāb’s biography will serve to problematize gender as a concept. While the fidāʾiyyīn were all power, all public, all spectacle, all gender as a discourse on power, the shabāb have very limited access to power and, as a result, gender does not function well to reflect their burdens. Showing me the scars in his body, results from the torture he was submitted to by the Syrians, Abu Fawzi, 62, an ex-Fattah commando, said: “I still have a very strong body. I did wrestling when I was younger. In our struggle, we never stop; we don’t retire. We fight until we die.” He told me about joining the revolution: “I joined the fidāʾiyyīn without my family knowing. When they found out, my mother cried a lot and my father forced me into my first marriage, hoping I’d leave the fidāʾiyyīn. But my marriage didn’t last. I gave up my wife, but not the thawra, the revolution.” Indeed, to be fit to fight for the motherland, Palestine, the fidāʾiyyīn had to detach themselves from another mother-land: home. The sphere of feminine domesticity is largely avoided by the fidāʾiyyīn when they narrate their heroic deeds. Abu Fawzi still thinks of himself as committed to the cause: “I go on thinking of myself as a fidāʾī. I never look back, only towards the future. And I never feel sorry for what I did.” I never had the courage to ask him a question that kept criss-crossing my mind while we were talking: “How is it to kill someone?” Indeed, it is very difficult not to bow in awe in the presence of a fidāʾī bragging about his deeds. But I knew that I could not go on providing an all-attentive and compliant audience to these narrations, because such discourses on hegemonic masculinity, present in the fidāʾiyyīn’s remembrances, cost the shabāb dear. Nawaf, 28, is as a clerical worker. All of his brothers were fidāʾiyyīn and he is very proud of them, commenting on how they carried their guns and defended the camp. Yet, he is perfectly aware that their heroic personas cannot simply be re-enacted by him. Nawaf was very generous when it came to sharing with me the challenges he faces in his love life. He first discovered the pleasures of sex through a European activist. When she returned to Europe, he did not have the means or the visas to follow her. Another European activist captured his attention shortly after, but he took the decision to put an end to the relationship. She had moved to Lebanon out of her conviction that she had to give her contribution to the Palestinian cause. This is what Nawaf told me about her: “You know, Gustavo, she loved Palestine in me. What she liked most about me is the Palestinian hero that I know I can’t afford to be.” The European’s departure had an awakening effect for him. Nawaf decided the time had come to be serious about his life. He regretted ignoring the needs of his family, while he was with the European. And there was a camp girl, Jamila. They started dating, away from the scrutinizing eyes of her family, but Jamila, knowing how much was at stake for a camp girl like herself, forced Nawaf’s meeting with her father so that the two could get engaged. The outcome was not what the two were hoping for. When I met Nawaf, he was still trying to recover from the break-up. Jamila’s father insisted that the couple married one year after the engagement, but Nawaf needed two years to finish his university. No agreement could be reached. When we talked, Nawaf was trying to figure ways to graduate fast and to build a house, so that he might still have a chance of marrying the love of his life. Now, I briefly highlight some of the theoretical implications of what I showed here. I start by telling another ethnographic vignette. Once I was attending an English class for adults at a Palestinian camp. The teacher spoke mainly in Arabic, because her students had limited command of English. At a certain point, she switched into English to say “gender equity” and returned to Arabic. I decided to provoke her: “You don’t actually have a word for gender in Arabic.” She replied: “Of course we do. It’s jins.” Me: “But jins is actually sex, no? It’s not gender. She answered: “Jins is sex; jins is also gender. There isn’t a problem here, all right?” Actually, late 20th-century theorists have argued that there is a problem there and that sex should be differentiated from gender. Differently from the supposedly natural and unchanging sex, gender could be modified and opened space for political mobilization. Anthropologists, sociologists, and philosophers demonstrated how the social constructions of the differences between men and women – or gender - were constitutive of inequalities that needed to be denaturalised. These inequalities soon enough served to establish a hierarchy in terms of different access to power by men and women. This mesmerisation by power reached its peak among researchers of masculinity, and prominently so among scholars of the Middle East. In the work of these scholars, the mesmerisation by power blended into a mesmerisation by the spectacle conducted in public. Inhorn (2012) lists some of the features characterizing this “hegemonic masculinity, Middle Eastern style”: patriarchy; polygyny; hyper-virility; tribalism; violence; militarism; and Islamic jihad. The experiences of the Shatila shabāb with their very limited access to power find no comfortable place within this theoretical framework. As a matter of fact, within this framework, defined as it is by a notion of gender as characterizing different access to power by men and women, non-homosexual men with limited power become invisible. Or else their masculinity needs to be in crisis. And yet it is not. The idea that men in very specific parts of the world are in crisis and cannot live up to the demands of an atavistic, misogynist and hyper-sexual masculinity feeds terrorology industries in the service of empire. Shatila shabāb’s masculinity is neither threatened by their predicaments nor are they terrorists in the making. Actually, non-homosexual Muslim men with limited access to power constitute the abject Other of liberal feminism and some LGBTIQ movements and that is the reason why they are re-traditionalised and their masculinity is stigmatized. I propose a reason for that: the fact that men like the Shatila shabāb who show how vulnerable they can be to others – a father, a father-in-law, a mother, a girlfriend – is so disturbing because there is a modernist rejection to the possibility that vulnerability to others can be a legitimate way of living a relationship. Where does this lead us? I wrap up my discussion by suggesting that there may be other ways of conceptualising the sex/gender complex. Sex, as a concept, works for the naturalization of the differentiation between male and female, even though this naturalization has no foundation in reality without remainder, as attested by the multitude of intersexed bodies. In the case of gender as a concept, this differentiation becomes an opposition, and furthermore an opposition of a hierarchical kind, based on different access to power by men and women. But let us try to learn something from the English teacher from the Palestinian camp I wrote about a few paragraphs back. She told us that jins is sex and that jins is gender. Jins then offers enough flexibility to accommodate both concepts. Arabic speakers know that jins also admits other renditions into English, such as race, class, and nation. I obviously do not want to reduce the sex/gender complex to its linguistic dimension, but there is something at play here that deserves attention. Jins can be sex, gender, class, race, and nation because it brings together those who pertain to the same kind. Rather than putting in relief the opposition between groups, jins emphasizes similarities and belonging together. When I suggest that we take proper note of this rendition of the sex/gender complex through the notion of jins, what I want is to call attention to the need to culturalize the complex, opening it up to properly reflect our ethnographic findings, which is what I did through the biographies of the fidāʾiyyīn and the shabāb. References Barbosa, Gustavo. 2022. The Best of Hard Times: Palestinian Refugee Masculinities in Lebanon. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Inhorn, Marcia. 2012. The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies, and Islam in the Middle East. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2022

|

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder, except for the inclusion of quotations properly cited.

Published in Vienna, Austria by ROR-n.