|

By Monika Mokre It was at the end of the 1990s when the EU once again realized that it was not able to act unilaterally and in solidarity in times of crisis. While this had already become obvious regarding the war in Bosnia and the genocide there, the Kosovo crisis, and the influx of refugees due to it was another case in point. Basically, these and other failures showed that, after then 50 years of European integration, nationalism of the Member States still prevailed. Thus, in 2001 the “Temporary Protection Directive”[1] was issued. In its contents, it provides a pragmatic and effective solution for times in which the asylum systems of Member States are overwhelmed by the number of refugees. For a period of one to three years, those concerned by the directive shall hold a residence permit including the right to accommodation, health services, social services, education, and access to the labour market. In order to distribute the burden of this situation, displaced persons can be transferred between Member States if the respective Member States as well as the persons concerned agree. In its procedures, the Directive follows the usual legislative procedure of the EU: the existence of a mass influx of refugees has to be established in a proposal by the Commission which is then decided upon by the Council of the European Union with qualified majority voting (i.e., a majority of states representing a majority of the population of the EU). Until early March 2022, the Directive has never been used in the more than 20 years of its existence although its implementation was discussed three times: In 2011, Italy and Malta called for its activation due to the high influx of refugees in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, especially from Libya. In the crisis of 2015, UNHCR and some Members of the European Parliament proposed to make use of it. And in 2021, EU foreign policy official Josep Borrell discussed the possibility of invoking the directive to aid Afghan refugees following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. In none of these cases, the European Commission saw the need for a proposal, probably due to the resistance of those Member States not directly affected by the situation. Due to its obvious dysfunctionality, the Commission proposed in 2020 to repeal the directive and to replace it by a regulation[2] as part of the foreseen “Pact on Asylum and Migration”. This directive could be implemented by the Commission without inclusion of the Council and would focus on the respective Member State facing a mass influx of refugees. The regulation would allow for temporary protection without asylum procedures as well as for increased possibilities for asylum procedures at the border. These accelerated asylum procedures at the border form a prominent and highly problematic part of the foreseen pact. Inter alia, it is foreseen that “in normal times”, persons from a country with less than 20% positive asylum decisions (in EU average) can be rejected in such a fast-track procedure. According to the directive, in times of crisis, persons from a country with less than 75% positive asylum decisions could be rejected at the border. The regulation also refers to general solidarity measures according to which Member States have either to accept a certain number of asylum seekers (calculated on the base of population and GDP) or deliver a financial contribution, the latter inter alia on the base of “return sponsorships”, i.e., organizing and financing voluntary or involuntary return to the country of origin. As the whole “Pact on Asylum and Migration”, this regulation has not been issued yet. Instead, the Directive of 2001 has been activated for the first time in its history and in an incredibly short time. For once, the EU has shown an ability to speak with one voice, overcoming at this point the nationalism of the Member States. It is easy to understand the reasons for this unprecedented situation. First, an external enemy has always been the most effective means to create and re-enforce a feeling of collective identity. Even the preamble of the Council Decision refers to the invasion undermining “European and global security”. Second, this new influx of refugees concerns first and foremost those countries who have always been opposed to every form of EU solidarity in accepting refugees, i.e., the Višegrad states Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary as well as Austria. Thus, while it is laudable and of utmost importance that Ukrainian citizens will be able to enjoy temporary protection in the EU, the most recent EU policies do not show a rejection of nationalist principles but, rather, a new application of them, enlarged by EU supra-nationalism. Again, EU refugee politics do not focus on people in danger but on its own interests. For the time being, these interests have shifted – from a general rejection of refugees to the protection of a specific group of refugees. And this group is very specific. It includes Ukrainian citizens, persons under international protection in Ukraine and the families of these two groups. Persons with a permanent residence in the Ukraine who “are unable to return in safe and durable conditions to their country of origin” should also get protection – either according to the Council Decision or in another national form. Persons with a temporary residence in Ukraine not able to return to their country of origin – e.g., students or workers, but also asylum seekers – may be granted protection according to the Decision. The – legally not binding – introduction to the Decision recommends that they should at least be allowed visa free entry in the EU in order to return to their country of origin. People with a – permanent or temporary – residence in the Ukraine who could return to their country of origin without being in danger are not mentioned at all. The proposal of the Commission went beyond the very narrow scope of the final decision: it included everybody “unable to return in safe and durable conditions to their country of origin” as well as everybody with a long-term stay in Ukraine, irrespectively of the conditions in the country of origin. This would have made a significant difference as many inhabitants of Ukraine do not hold Ukrainian citizenship. There were 76.000 foreign students in Ukraine, nearly a quarter of them from Africa. And as I am writing this, there is increasing information about BIPoC[3] hindered to leave Ukraine or to enter another country, especially Poland. In both these countries, fascist groups have been active for a long time and continue to be very present. Also, people who transported BIPoC to the EU face police persecution due to human trafficking. It should also be mentioned that about 400.000 Roma who live in Ukraine also face racist discrimination including fascist attacks when trying to cross borders. Furthermore, according to UN figures, about 30.000 of them do not have documents; thus, their chance of being accepted under the conditions of the directive are slim[4]. Finally, it remains to be seen how the mass influx of refugees from Ukraine will affect those from other countries asking for asylum in the EU. Especially in this regard, it is important that the directive is still in force and not the foreseen regulation. If all asylum seekers from countries with less than 75% of positive decisions were subjected to the fast-track procedure, only people from Venezuela, Syria, and Eritrea would have a chance for a proper asylum procedure. But also without these stipulations, more and more asylum claims have been decided negatively after a very superficial assessment of flight reasons even before the war – at least in Austria. People are dying in the war in Ukraine – people from different nationalities, including from the Russian Federation. People are fleeing to save their lives – people living in the Ukraine and also Russian citizens opposed to the war. These people must be protected – this is enshrined in the Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Convention and the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, irrespectively of their nationality, ethnicity, gender, class etc. There is no doubt that the decision to activate the Directive on Temporary Protection is an important step here. But there is also no doubt that the limitations of this decision contradict these fundamental principles and are driven more by nationalist and supranationalist concepts and interests than by a truly universal understanding of human rights – including the rights of those who, out of which reason ever, are not residents of the country of which they hold the citizenship. The European Union understands the “four mobilities” including mobility of persons, as one of its most important values and achievements. But when it comes to the protection of refugees and the rights of migrants in the EU, individual mobility leads to exclusion. Third country citizens in the EU lose their right to citizenship in a Member State when they spend some time in another Member State. Afghan refugees who spent their whole life in Iran do not receive protection as they are not persecuted in their country of origin. And now, the Council of the European Union simply ignores the plight of those who decided voluntarily to make Ukraine their new home. Probably, its limited approach made it possible to implement the directive without protest of right-wing parties. In this vein, the Austrian right-wing party FPOe recently published the slogan: “War refugees, yes, hidden mass migration, no.” And in social media, those usually opposed to any kind of protection for people on the move welcome Ukrainian refugees as they are “white and our European brothers and sisters”. Maybe one should mention at this point that the full-hearted acceptance of Ukraine as a part of Europe is a rather recent development directly related to the definition of a common enemy. Up to now, it has, e.g., not applied to the many exploited Ukrainian workers in EU agriculture. And, maybe one should also mention that in the same week that Russian forces entered Ukraine, the US launched airstrikes in Somalia, Saudi Arabia bombed Yemen, and Israel struck Syria and Palestinians in Gaza. We did not hear much about that. Notes: [1] Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof; https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2001:212:0012:0023:EN:PDF [2] Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of The Council addressing situations of crisis and force majeure in the field of migration and asylum, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020PC0613&from=EN [3] Black indigenous people of colour [4] https://ukraine.un.org/en/106824-about-30000-roma-ukraine-have-no-documents-story-roma-activist

0 Comments

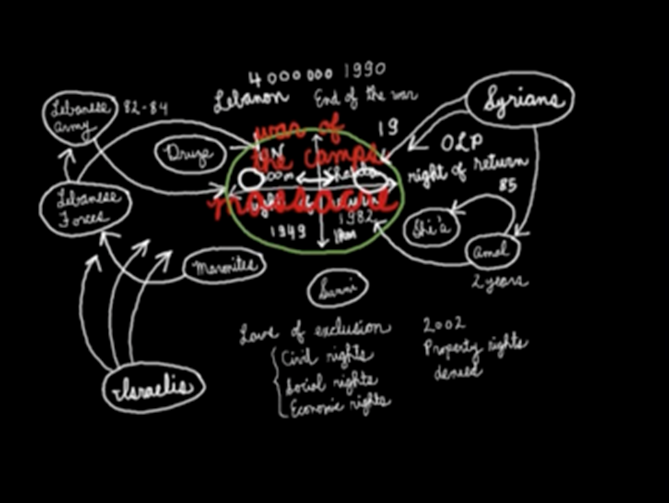

By Gustavo Barbosa *This essay presents one of the arguments developed by the author in his book The Best of Hard Times: Palestinian Refugee Masculinities in Lebanon (Barbosa, 2022). In this short essay, I argue for the full historicity and pliability of masculinity, which changes from place to place and time to time. Based on fieldwork conducted in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in the southern outskirts of Beirut, where I lived for one year and conducted research for two, I demonstrate that the shabāb, the lads from the camp, faced with unemployment and the de-mobilization of the Palestinian Resistance movement, in its military form, cannot replicate the heroic persona of their forebears, the fidāʾiyyīn, who exude virility when narrating their deeds. As may be implied from this already, based on shabāb’s biographies, I problematize what Marcia Inhorn (2012) has ironically labelled “hegemonic masculinity, Middle Eastern style.” I develop my argument in three moves. First, I provide the reader with historic scaffolding, so that s/he can understand not only why masculinity has changed from one generation to the next, but also why gender, as a concept imbued with notions of power, works well to describe the fidāʾiyyīn’s lives, but not the shabāb’s. Second, I provide some ethnographic evidence to this argument. I finish by addressing some of the theoretical implications of my reasoning. For the historic scaffolding, I quote from what I consider as the best documentary about Shatila, the movie Roundabout Shatila (2005), by Maher Abi Samra. Even though a bit dated, the quote, illustrated by the film frame below, shows how Shatila is placed at the centre of various circles of causation, all highly complex. That means, in practice, that Shatilans today, including the shabāb, have very little control of what at the end comes to determine their lives. Figure 1 – Frame from the movie Roundabout Shatila, by Maher Abi Samra “Shatila Camp, one kilometer long and 600 meters large, is located in the outskirts of the southern suburb of Beirut. In 1949, the UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Middle East) leased the camp in order to house the Palestinian refugees waiting for their right of return. Lebanon is a sectarian society of approximately four million people and 19 religious communities. The principal ones are the Shiites, the Maronites, the Sunnites and the Druze. These communities have always relied on alliances with powerful foreign countries to protect their own interests. Consequently, the Israelis and the Syrians continue to play a leading role in Lebanon. In 1982, the Israeli Army invades Lebanon. The PLO (the Palestinian Liberation Organization) is forced to leave Lebanon. Maronite militias, known as the Lebanese Forces, backed by the Israelis, commit the Sabra and Shatila massacres. It is the end of one period and the beginning of another. The official Lebanese Army, backed by the Lebanese Forces, surround the camp of Shatila between 1982 and 1984. During this period, the Army conducts forcible house searches and massive arrests. In 1985, Amal, the Shiite militia, backed by the Syrian regime, start the War of the Camps and surround the camp for two years. Two years later, Amal can still not retain Shatila. Palestinian organizations, backed by the Syrians, start an internal conflict between Palestinians, which ends with total Syrian regime control of the camp that continues to this day. 1990 marks an end to the Lebanese Civil War. Shatila is still under Syrian control. The laws which deprive Palestinians of their civil rights, social rights, and economic rights are enforced again. Though deeply divided on other issues, Lebanese society holds the Palestinians solely responsible for the Civil War. In 2002, the majority of the Lebanese Parliament votes to deny the right of property to Palestinians. The pretext invoked is to protect the Lebanese identity and the stability of the sectarian system, but the underlying reason is to retain the Palestinians’ right of return. Shatila and other refugee camps in Lebanon have become the scapegoat of Lebanese society.” Two different iconic figures are associated with each of these historic periods. As shown in the quote from Abi Samra’s movie, the important year to remember here is 1982, the definitive turning point in this saga. Before that year was the period that Palestinians refer to as the golden days of the revolution, the ayyām al-thawra, their moment of strength in Lebanon. The iconic figure associated with this period is the resistance fighter, the fidāʾī. The very word means the man who is willing to sacrifice himself, in the fight to reconquer the motherland. Posters from this period often celebrated this figure, portraying him in all his courage and pride walking on the crest of hills, a kuffiyya, the Arab strap around his shoulders, and a bunduqiyya, the Kalashinikov machine-gun in his hand, proceeding to military incursions deep into Palestine. With the end in 1982 of the days of the revolution, the iconic figure became the camp shāb, the lad from Shatila, who cannot act as a fighter, because the Palestinian Resistance Movement was de-mobilized, and who cannot find a job either and, as a result, needs to postpone marriage plans. The changes in the iconic figures of these two periods – the brave fidāʾī and the shāb with very limited access to power – speaks to the full historicity and pliability of masculinity. In Palestine, before 1948, a man would come of age and display his gender belonging by marrying, starting an independent household and bearing a son. For the Palestinian diaspora in Lebanon, prior to 1982, acting as a fidāʾī provided an alternative mechanism for men to come of age and display gender belonging. But, then, what happens to today’s shabāb, who cannot act as male providers for the families they wish to start or act as fighters? Based on the specialized literature, the traditional answer to this question is that the shabāb are emasculated, that their masculinity is in crisis because they cannot live up to the requirements of an ideal-typical hegemonic masculinity. But, by living with them in Shatila, I did not get the feeling that they thought that their masculinity was menaced. So, rather than freezing ideals of masculinity and creating crisis by heuristic fiat, I decided, following Inhorn’s advice, to nuance the discussion of the masculine ideal, opening it up to the findings of my ethnography. At the end, these findings prompted me to provoke another crisis, of an epistemological nature: the crisis of gender as a concept. The time has come to populate this history and this discussion with ethnography and real life. A fidāʾī’s and a shāb’s biography will serve to problematize gender as a concept. While the fidāʾiyyīn were all power, all public, all spectacle, all gender as a discourse on power, the shabāb have very limited access to power and, as a result, gender does not function well to reflect their burdens. Showing me the scars in his body, results from the torture he was submitted to by the Syrians, Abu Fawzi, 62, an ex-Fattah commando, said: “I still have a very strong body. I did wrestling when I was younger. In our struggle, we never stop; we don’t retire. We fight until we die.” He told me about joining the revolution: “I joined the fidāʾiyyīn without my family knowing. When they found out, my mother cried a lot and my father forced me into my first marriage, hoping I’d leave the fidāʾiyyīn. But my marriage didn’t last. I gave up my wife, but not the thawra, the revolution.” Indeed, to be fit to fight for the motherland, Palestine, the fidāʾiyyīn had to detach themselves from another mother-land: home. The sphere of feminine domesticity is largely avoided by the fidāʾiyyīn when they narrate their heroic deeds. Abu Fawzi still thinks of himself as committed to the cause: “I go on thinking of myself as a fidāʾī. I never look back, only towards the future. And I never feel sorry for what I did.” I never had the courage to ask him a question that kept criss-crossing my mind while we were talking: “How is it to kill someone?” Indeed, it is very difficult not to bow in awe in the presence of a fidāʾī bragging about his deeds. But I knew that I could not go on providing an all-attentive and compliant audience to these narrations, because such discourses on hegemonic masculinity, present in the fidāʾiyyīn’s remembrances, cost the shabāb dear. Nawaf, 28, is as a clerical worker. All of his brothers were fidāʾiyyīn and he is very proud of them, commenting on how they carried their guns and defended the camp. Yet, he is perfectly aware that their heroic personas cannot simply be re-enacted by him. Nawaf was very generous when it came to sharing with me the challenges he faces in his love life. He first discovered the pleasures of sex through a European activist. When she returned to Europe, he did not have the means or the visas to follow her. Another European activist captured his attention shortly after, but he took the decision to put an end to the relationship. She had moved to Lebanon out of her conviction that she had to give her contribution to the Palestinian cause. This is what Nawaf told me about her: “You know, Gustavo, she loved Palestine in me. What she liked most about me is the Palestinian hero that I know I can’t afford to be.” The European’s departure had an awakening effect for him. Nawaf decided the time had come to be serious about his life. He regretted ignoring the needs of his family, while he was with the European. And there was a camp girl, Jamila. They started dating, away from the scrutinizing eyes of her family, but Jamila, knowing how much was at stake for a camp girl like herself, forced Nawaf’s meeting with her father so that the two could get engaged. The outcome was not what the two were hoping for. When I met Nawaf, he was still trying to recover from the break-up. Jamila’s father insisted that the couple married one year after the engagement, but Nawaf needed two years to finish his university. No agreement could be reached. When we talked, Nawaf was trying to figure ways to graduate fast and to build a house, so that he might still have a chance of marrying the love of his life. Now, I briefly highlight some of the theoretical implications of what I showed here. I start by telling another ethnographic vignette. Once I was attending an English class for adults at a Palestinian camp. The teacher spoke mainly in Arabic, because her students had limited command of English. At a certain point, she switched into English to say “gender equity” and returned to Arabic. I decided to provoke her: “You don’t actually have a word for gender in Arabic.” She replied: “Of course we do. It’s jins.” Me: “But jins is actually sex, no? It’s not gender. She answered: “Jins is sex; jins is also gender. There isn’t a problem here, all right?” Actually, late 20th-century theorists have argued that there is a problem there and that sex should be differentiated from gender. Differently from the supposedly natural and unchanging sex, gender could be modified and opened space for political mobilization. Anthropologists, sociologists, and philosophers demonstrated how the social constructions of the differences between men and women – or gender - were constitutive of inequalities that needed to be denaturalised. These inequalities soon enough served to establish a hierarchy in terms of different access to power by men and women. This mesmerisation by power reached its peak among researchers of masculinity, and prominently so among scholars of the Middle East. In the work of these scholars, the mesmerisation by power blended into a mesmerisation by the spectacle conducted in public. Inhorn (2012) lists some of the features characterizing this “hegemonic masculinity, Middle Eastern style”: patriarchy; polygyny; hyper-virility; tribalism; violence; militarism; and Islamic jihad. The experiences of the Shatila shabāb with their very limited access to power find no comfortable place within this theoretical framework. As a matter of fact, within this framework, defined as it is by a notion of gender as characterizing different access to power by men and women, non-homosexual men with limited power become invisible. Or else their masculinity needs to be in crisis. And yet it is not. The idea that men in very specific parts of the world are in crisis and cannot live up to the demands of an atavistic, misogynist and hyper-sexual masculinity feeds terrorology industries in the service of empire. Shatila shabāb’s masculinity is neither threatened by their predicaments nor are they terrorists in the making. Actually, non-homosexual Muslim men with limited access to power constitute the abject Other of liberal feminism and some LGBTIQ movements and that is the reason why they are re-traditionalised and their masculinity is stigmatized. I propose a reason for that: the fact that men like the Shatila shabāb who show how vulnerable they can be to others – a father, a father-in-law, a mother, a girlfriend – is so disturbing because there is a modernist rejection to the possibility that vulnerability to others can be a legitimate way of living a relationship. Where does this lead us? I wrap up my discussion by suggesting that there may be other ways of conceptualising the sex/gender complex. Sex, as a concept, works for the naturalization of the differentiation between male and female, even though this naturalization has no foundation in reality without remainder, as attested by the multitude of intersexed bodies. In the case of gender as a concept, this differentiation becomes an opposition, and furthermore an opposition of a hierarchical kind, based on different access to power by men and women. But let us try to learn something from the English teacher from the Palestinian camp I wrote about a few paragraphs back. She told us that jins is sex and that jins is gender. Jins then offers enough flexibility to accommodate both concepts. Arabic speakers know that jins also admits other renditions into English, such as race, class, and nation. I obviously do not want to reduce the sex/gender complex to its linguistic dimension, but there is something at play here that deserves attention. Jins can be sex, gender, class, race, and nation because it brings together those who pertain to the same kind. Rather than putting in relief the opposition between groups, jins emphasizes similarities and belonging together. When I suggest that we take proper note of this rendition of the sex/gender complex through the notion of jins, what I want is to call attention to the need to culturalize the complex, opening it up to properly reflect our ethnographic findings, which is what I did through the biographies of the fidāʾiyyīn and the shabāb. References Barbosa, Gustavo. 2022. The Best of Hard Times: Palestinian Refugee Masculinities in Lebanon. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Inhorn, Marcia. 2012. The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies, and Islam in the Middle East. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

By Viola Castellano Despite existing for several decades, voluntary return programs for migrants and asylum seekers became an essential part of the 2020 EU Pact for Migration and Asylum. In the words of EU Vice-President Margaritis Schinas,[i] the program for Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration became “One of the pillars of the new ecosystem we are building on returns, to the mutual benefit of the returnees, the EU and third countries”. Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration programs (AVRR) provide recipients with free transportation back to their countries of origin, and an initial financial/counseling/logistical support to re-start their lives there. These programs are generally coordinated by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) with the support of other humanitarian and co-developmental organizations. They are operated from the countries migrants encounter on their undocumented routes to Europe (the so-called transit countries) and from EU countries. They are sponsored either by the European state from where the return is made, or by international funds such as the European Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). According to the IOM, voluntary return is based on the voluntary decision of the individual which in turn is composed of two elements: freedom of choice - meaning lack of physical, psychological, material pressure - and informed decision. One of the issues I investigate in my current research on post-asylum subjectivities, is related to how AVRR programs work in the case of The Gambia, the smallest country of continental Africa with a population of two million people. Despite its modest size, in the last decade, more than 70,000 Gambians applied for asylum in European countries, after traveling mainly through the Central Mediterranean Route. The asylum authorities of the various European countries tended to label Gambian asylum seekers mainly as “economic migrants”, even more so after the autocratic and violent regime of Yaya Jammeh ended in 2017 and democracy was restored in the country. This left them undocumented, in legal limbo, and at risk of being repatriated to The Gambia. In addition to Gambians who reached Europe, many more were blocked in the various African transit countries. The number of “stranded” Gambian migrants increased in the last 5 years as a result of: EU and African countries’ agreements on measures to tackle irregular migration through return, deportation, and border externalization, made in the Valletta EU-Africa Summit in 2015 (Pace, 2016); the restoration of the bilateral agreements between Italy and Libya in 2017 to prevent migrants from reaching European shores through the reinforcement of the so-called Libyan coastguard; and, finally, due to Covid-19, which further complicated Search And Rescue (SAR) operations by NGOs in the Mediterranean. The acts of violence that sub-Saharan migrants suffer along the Central Mediterranean Route, and especially in Libya, have been widely reported by humanitarian organizations, with 85% of refugees and migrants suffering torture and inhumane or degrading treatment (Medici per I Diritti Umani-MEDU). Due to these factors, Gambian (and other) migrants stuck in dangerous conditions in transit countries, or those with no chance of regularization in Europe, became privileged candidates for Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration programs. Once back in The Gambia, AVRR programs treat returnees as victims of irregular migration in need of empowerment through self-entrepreneurship, with the goal of discouraging irregular migration by combatting the widespread local stigmatization of “failed returnees” (Schuster, L., & Majidi, 2015). Returnees, indeed, especially the ones repatriated from Libya, are nationally constituted as a political problem, because of the widespread stigmatization they are subjected to, as failed migrants who wasted family resources. This adds up to the general association of deportation with criminality, and to moral suspicion towards those who experienced the violent dynamics dominating the "backway" (the Gambian term to designate the undocumented trip to Europe). Their failure and their traumas accumulated along the journey are therefore perceived as a threat to a country that saw its structural poverty and unemployment worsening in the last decades. In the public eye, their alleged desperation makes them more likely to engage in criminal activities and more mentally unstable. As much as traveling to Europe is seen as a form of social and economic prestige (Schapendonk, 2017), the financial, existential, and emotional cost of the journey, when it is not successful and does not produce wealth to redistribute within the community, becomes a disadvantage, a stigma. This is why IOM and other organizations’ goal is to revert the imaginary around return and deportation (Fine and Walters 2021). In my research, I observed how, with that goal in mind, IOM depicts AVRR returnees as direct victims and witnesses of the perils of “irregular migration” and of human trafficking. On the one hand, their status, as stressed by Fine and Walters, is seen as a resource and a voice against “irregular migration”, and they are often involved in (paid) activities of sensitization in villages and cities, sponsored by the same IOM and other international organizations and NGOs. On the other hand, they are promoted as enthusiastic self-entrepreneurs and coached through programs in business administration and various work skills in locally contracted companies and agencies. Their “success stories” are presented as living proof of the benefits of homecoming and the possibility of “making it” in The Gambia.[ii] In the interviews[iii]I collected, I observed how some of the returnees embraced the subjectivity promoted by IOM and EU partners, engaging in sensitization activities and complying with the self-entrepreneurial ethos envisioned by AVRR programs. I also observed how others, instead, preferred not to go back to their village and hide in the metropolitan areas. They were too ashamed to face their families and were willing to embark on the journey again as soon as they had the possibility. IOM and other organizations administering AVRR switched to the direct funding of returnees’ “business plans” once they realized that their previous funding scheme left returnees employed to pay for another trip towards Europe. These business plans, which they need to present to obtain the reintegration funds, are aimed to initiate a new career path in The Gambia. Finally, a third group, mainly constituted by returnees from Libya, strongly politicized their social location and questioned how the Gambian government and its EU partners were managing the issue of returnees, arguing that the humanitarian assistance provided by OIM reintegration programs was not sufficient,. The efficiency of the AVRR programs indeed has increasingly been criticized by various humanitarian organizations, as well as by returnees themselves. They were labeled as a form of soft deportation (Andrijasevic, 2010; Brachet, 2018; Kalir, 2017), due to the lack of choice of undocumented migrants in such “voluntarily” returns. The questionable degree of voluntariness of these programs is well demonstrated by the fact that they are most successful in dangerous transit countries such as Libya or in European countries where deportations are consistently implemented.[iv] In the campaigns against “irregular migration”, its own engendered violence is presented as immanent to the moral feature of illegality connected to the mobility effort and to the smuggling network. While presenting the (il)legal violence of undocumented migration as an exceptional form of suffering, these initiatives remove their genealogy and the active role of Europe in what has been called the mobility regime (Glick Schiller and Salazar, 2013). In conclusion, for European countries, the promotion of voluntary repatriation constitutes another tool in pursuing border externalization through agreements with countries of origin, negotiating economic aid in return of repatriation deals, meanwhile formally responding to the humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean. However, for Gambian asylum seekers caught in bureaucratic mazes with no chance of regularization in Europe, and for the ones who are stuck in detention centers in Niger and Libya, voluntary repatriation is rather experienced as forced choice. This is a crucial element that often invalidates AVRR programs’ appeal to the idea of choice for the neoliberal subject (Crane and Lawson 2020) and their intention to change the social imaginary of deportation. References Andrijasevic, R. (2010). DEPORTED: The Right to Asylum at EU’s External Border of Italy and Libya 1. International Migration, 48(1), 148-174. Brachet, J. (2018). Manufacturing smugglers: From irregular to clandestine mobility in the between exclusion and inclusion. Antipode, 50(3), 783-803 Crane, A., & Lawson, V. (2020). Humanitarianism as conflicted care: Managing migrant assistance in EU Assisted Voluntary Return policies. Political Geography, 79, 102-152. Fine, S., & Walters, W. (2021). No place like home? The International Organization for Migration and the new political imaginary of deportation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1-18. Glick Schiller, N., & Salazar, N. B. (2013). Regimes of mobility across the globe. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 39(2), 183-200. Kalir, B. (2017). Between “voluntary” return programs and soft deportation. Return migration and psychosocial wellbeing, 56-71. Pace, R. (2016) "The trust fund for Africa: a preliminary assessment." Technical Report. Schapendonk, J. (2017). The multiplicity of transit: the waiting and onward mobility of African migrants in the European Union. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies, 3(2-3), 208-227 Schuster, L., & Majidi, N. (2015). Deportation stigma and re-migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(4), 635-652 Notes [i] “Press remarks by Vice-President Schinas on the EU's Voluntary Return and Reintegration Strategy” of 27/04/202: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_21_1991 [ii] Tekki Fi, which is the name of the EUTF sponsored program of economic development addressed to Gambian youth and return migrants, means indeed “to make it” in Wolof: https://www.tekkifii.gm/about [iii] I conducted research in The Gambia in November and December 2019. During that period I collected 26 interviews among government officials, IOM and NGOs workers and directors, voluntary and forced returnees and their family members. I conducted two focus groups with the students of the University of the Gambia on the right to asylum and participant observation in a family of a returnee with whom I lived for two weeks. The pandemic disrupted the possibility of returning to Gambia in 2020 and 2021 as planned, but I nevertheless conducted 12 online interviews with some of the people I previously met in the 2019 fieldwork. [iv] As stated in the IOM Gambia AVRR webpage, 90% of voluntary returns in The Gambia were operated by the EU Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration. Among them, 2,992 Gambians returned from Libya, another 1,392 from Niger and 618 more stranded along key migration routes in Africa and in Europe. Please refer to: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-hits-milestone-5000-gambians-supported-assisted-return

|

Archives

June 2022

|

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder, except for the inclusion of quotations properly cited.

Published in Vienna, Austria by ROR-n.